NEW YORK — In most major American cities, guns recovered in criminal investigations tend to come from gun shops and sellers in that same state, data show.

Not in New York City.

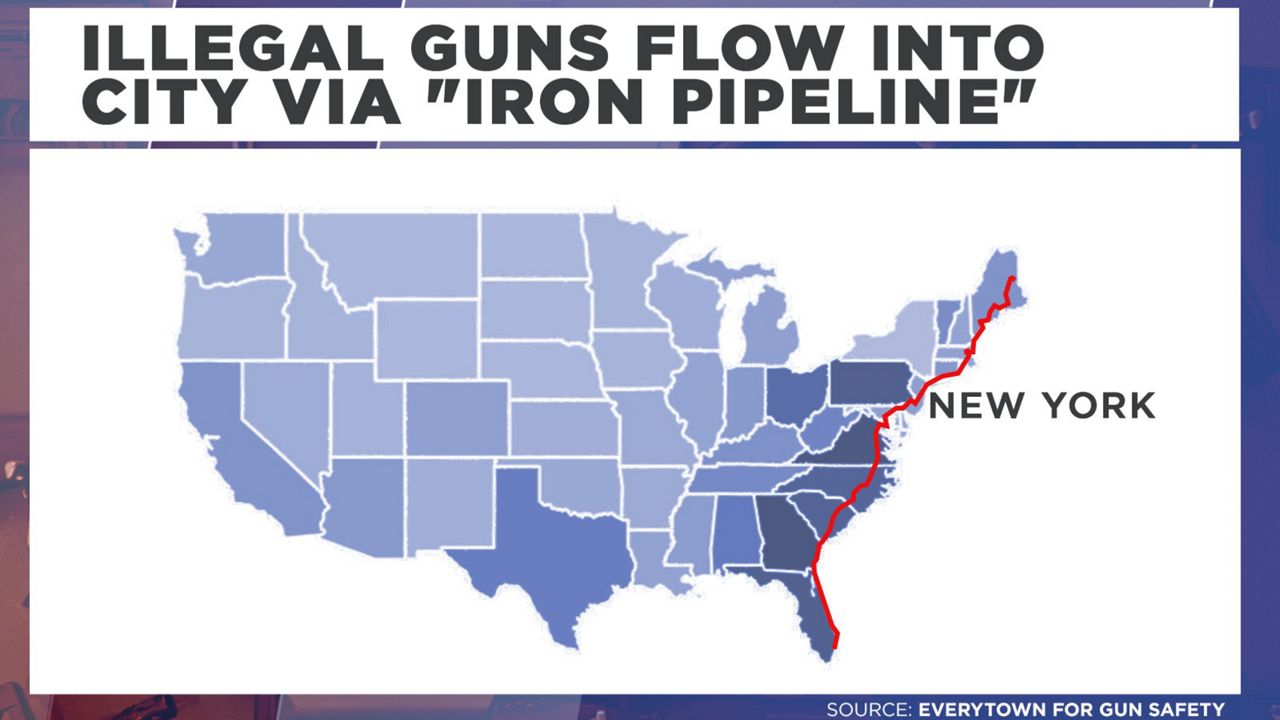

Despite having some of the strictest gun possession laws in the country, New York City is the endpoint for a funnel of guns illegally trafficked from states to the south, up Interstate 95 — the so-called “Iron Pipeline” that experts say enables criminal violence in the city.

More than half of guns recovered in the city in recent years have been traced to Florida, Georgia, North and South Carolina, Virginia and Pennsylvania, according to law enforcement analyses.

The pipeline is not new, but elected leaders and police officials are drawing more attention to it amid a spike in gun violence in the city and after a string of high-profile shootings of police officers, including the death last week of Officer Jason Rivera in Harlem.

"We must stop the flow of illegal guns in our city," Mayor Eric Adams said in a speech Monday announcing his plan to combat gun violence. "The 'iron pipeline' must be broken."

Experts say that the city has limited ways to address the flow of guns without stronger federal laws. But even in the midst of a pandemic that has eroded much of the city’s social supports and cratered economic opportunities in low-income areas, shutting down the pipeline would have an enormous impact on violence.

“No matter what sort of social ills we have, they're going to be more serious in an environment awash in illegal firearms,” said David Kennedy, a professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

Nationwide, the pandemic has been accompanied by a rise in crime, including violent crime and shootings. New York City has seen two of its most violent years in more than a decade, and the new year has brought rising violence as well.

So far this year, the city has seen 52 shooting incidents, compared with 45 for the same period in 2021, according to NYPD data. Five police officers have been shot this year, including Rivera. Seven officers were shot in the city in 2021, the New York Post reported.

Experts say that traffickers using the “Iron Pipeline” are likely providing the majority of guns used in criminal shooting incidents.

The typical trafficking case in New York City sees a local resident with a driver’s license from a southern state drive down, pick up guns — typically handguns — and drive them back to the city for distribution. In states without mandatory background checks, residents can typically purchase as many guns as they want from gun shops. Purchases have even less scrutiny at gun shows, where federal investigators cannot monitor secondary market purchases.

Guns are also stolen at higher rates in states with weak gun laws, and are frequently trafficked into cities and recovered in criminal incidents. The gun used to kill Rivera and gravely wound a second officer, Wilbert Mora, was reported stolen in Baltimore in 2017, police officials said this weekend.

While there are some trafficking operations that move guns in large volume, guns also come from small-time suppliers who may make one or two trips south a year, according to Nick Suplina, the senior vice president for law and policy at Everytown for Gun Safety.

Suplina co-authored a report from Attorney General Letitia James on gun trafficking data from 2010 to 2015, which found that nearly 60% of guns recovered in New York City came from I-95 states.

Law enforcement agencies, like the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, have overall very little insight into the trafficking pipeline. That’s due to efforts by the gun lobby to resist legislation that would expand the ATF’s ability to maintain a nationwide database of gun purchases, and exercise stronger control over the secondary market, Kennedy said.

“We have effectively extraordinarily limited capacity either to understand or act on the rivers of guns that come into New York City illegally, and that is a deliberate result of public policy,” he said.

That makes it difficult to understand the relationship between trafficking and violence: Does worsening crime create a market for trafficked guns, or are crime waves preceded by a rush of illegal firearms?

Recent data from the ATF suggest that more guns being recovered in New York City have a lower than usual “time to crime,” the time between when a gun is sold and when it is confiscated by police. That could mean that the spike in gun buying during the pandemic has downstream effects on crime.

“That doesn't mean they’re the cause of the spike in shootings,” Suplina said of recently bought guns. “But it does suggest that newly acquired guns and gun purchasing during the pandemic may be a contributing factor to the uptick in violence.”

James has suggested that gun trafficking plays a greater role in rising gun violence than changes to the city’s criminal justice system such as bail reform, which NYPD officials and conservative elected officials have said is at fault.

“There are a number of reasons why shootings go up and shootings go down,” Suplina said. “But there is no question, in my mind, that if you could eliminate the flow of illegal guns into New York City, you're going to have a safer city with few shootings.”

That needs to happen at the federal level, Suplina said, such as with nationwide mandatory background checks and a greater crackdown on gun sellers whose firearms are consistently found in crime scenes. Efforts by Democratic elected leaders to pass new gun control laws have mostly failed.

Last February, Rep. Carolyn Maloney, who represents parts of Manhattan, Queens and Brooklyn, reintroduced legislation dating to 2013 that would strengthen penalties for “straw purchasers” who act as middlemen in buying guns for people with criminal records, among other added protections. The legislation has six co-sponsors.

In June, Sen. Kristin Gillibrand joined with Mayor Adams to announce her plan to reintroduce the same legislation in the Senate, but has not done so yet. Gillibrand said Monday she plans to reintroduce the bill sometime this year.

Experts say that the city and the NYPD is relatively limited in how effectively it can face down the pipeline of trafficked guns without a major change to federal laws.

The NYPD made nearly 4,500 gun arrests in New York City, and says that determining the origin of the gun is part of its investigation. Suplina said that the NYPD and local prosecutors could use more resources to try and fold gun arrests into trafficking investigations, by building cases against the sellers of those guns.

In his speech Monday, Adams outlined a series of policing changes aimed at trafficking, including expanding an anti-violence unit that would operate in a semi-plainclothes status, asking the state to conduct checks of vehicles and people entering the city via tunnels, bridges and buses, and calling on the federal government to enact a series of new laws, such as universal background checks for gun purchases.

"These actions are only a start, but they will create critical momentum that will help New York City, and all cities," Adams said.

Targeted policing on trafficking is necessary, said Daniel Webster, a professor of public health policy at Johns Hopkins University who studies gun violence. But, he added, a return to blanket policing strategies like stop-and-frisk would only undermine those efforts.

Already, he said, communities and police departments are as alienated from one another as at any point in recent history, and police should consider communities as partners in getting illegal guns off the street.

“Law enforcement is gonna have to show that it can tackle the problem in front of them in ways that don't create broad harm to people who really aren’t threats,” Webster said.